War Stories 18

Enjoy the stories in this section. Some of them may even have been true!! Have a favorite war story you've been relating over the years? Well sit down

and shoot us a draft of it. Don't worry, we'll do our best to correct grammar, punctuation, and spelling before we publish it. to us and we'll publish them for all to enjoy.

Memories Undimmed by Time: FSB David- Cambodia -14 June 1970

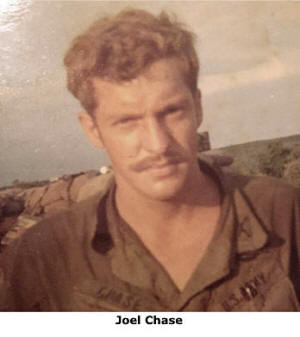

By Joel Chase and Terry McCarl

INTRODUCTION

By Terry A. McCarl, Historian, 15th Medical Battalion Association

As the Historian of the 15th Medical Battalion (BN) Association, I am

privileged to research, read, and write about the heroic and meritorious

acts of members of the 15th Medical Battalion. Such stories are abundant,

particularly Medevac helicopter rescue missions plus life-saving emergency

medical care at the 15th Med BN medical treatment facilities. The following

is a story about such a mission, but it is about much more than that. It is

a story of extreme courage, fortitude, endurance, and resourcefulness about

a young Army officer and his unit that found themselves in what must have

seemed like a hopeless situation.

I first met CPT Joel Chase and his wife, Dorothy, at the 15th Med BN

Association Reunion in Branson. MO, April 26-30, 2017. At one of the evening

informal get-togethers in the Hospitality Room, Joel asked if he could

address the group. Joel explained that he had been a Platoon Leader of D

Co., 1/5 Cav located at FSB David, about 10 miles inside the Cambodian

border. At 0300 on 14 June 1970, with a terrain challenging to defend and

out of range of supporting artillery, FSB David was attacked.

The

story, briefly, was that Joel was seriously wounded and taken to the B Co.

15th Medical Battalion medical treatment facility at FSB Buttons near Song

Be. He was unconscious during the period he was being transported to

FSB Buttons.

After he received emergency medical treatment at Buttons, a

Medevac helicopter flew him to the 24th Evacuation Hospital in Long Bien. He

was then transported to Japan and then home to the US. Miraculously, he

survived and was there in Branson, MO 47 years later, in 2017 to relate his

story.

That night Joel and his wife Dorothy expressed their

appreciation to the 15th Medical Battalion for saving his life. Their

presentation was very moving.

Three individuals who were involved in

Joel's medical treatment at the B Co. facility were at the reunion: 1LT Tom

Garnella, CPT Jon Lundquist, and SP5 Richard Schroder - more about them

later. Joel asked if anyone present at the gathering was with the Medevac

crew that hauled him from FSB David to FSB Buttons, but there was no

response.

I talked to Joel the next day, and he said that if

possible, he would like to get in contact with and personally thank the

Medevac pilots and crew members who rescued him from LZ David. I advised

Joel I would poll our membership to identify and locate these individuals.

I posted an inquiry on the 15th Medical BN Facebook page asking if

anyone knew who was on that crew. Dan Brady, medic, contacted me. He

said that it was the mission during his time in Vietnam that he remembers

the most vividly. We proceeded from there to identify the other crew members.

Joel's Vietnam tour began on 04 October 1969. In April of 1970, Joel had

completed six months of his VN tour and was eligible for transfer out of the

field to a relatively “safer” job. He chose instead to stay with his unit as

Platoon Leader. Then, in May of 1970, the Cambodian Incursion came about!

Here is Joel's story in his own words.

JOEL CHASE'S STORY

I was a platoon leader with the 1st Air Cav in 1969 and 1970

following graduation from OCS at Benning. When I got to Vietnam, I realized

OCS had not prepared me to be an infantry platoon leader, but I had

out-standing and understanding Non-Commissioned Officer Sergeants. It took

them a while to educate me, but I finally “got it” after about six months in

the brush. Then “Tricky Dick” gave us the green light to go kick some butt

in Cambodia, so the decision to stay with my platoon was an easy one.

I was a platoon leader with the 1st Air Cav in 1969 and 1970

following graduation from OCS at Benning. When I got to Vietnam, I realized

OCS had not prepared me to be an infantry platoon leader, but I had

out-standing and understanding Non-Commissioned Officer Sergeants. It took

them a while to educate me, but I finally “got it” after about six months in

the brush. Then “Tricky Dick” gave us the green light to go kick some butt

in Cambodia, so the decision to stay with my platoon was an easy one.

We were in the draw-down mode and weren't getting replacements for those

going home or wounded. At last count, my platoon was down to 17 guys,

including some short-timers and a couple of FNGs, and the bad guys in

Cambodia were formidable adversaries. They were well-armed, trained, fed,

and didn't run from a fight.

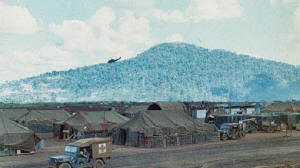

Battalion (1st of the 5th Cav) finally

took pity on our little company (D) and put us on the green line at Fire

Support Base (FSB) David, a tiny place 10 miles inside the border and

outside of artillery fan fire from other FSB's. The Cav had done severe

damage to the NVA caches and other infrastructure, which mightily pissed

them off. So they launched an all-out attack on David on 14 June 1970 at

0300. What their commanders didn't understand was that we were waiting for

them.

The first shot fired on David was from an M16 at about 0300. A

trip flare in my sector went off, and a guard on a bunker thought he saw

movement and fired one round at that spot. After visually scanning the area

for nearly 30 minutes without locating any enemy, we were about to give up

when a guy next to me thought he saw something and pointed to it just inside

the concertina wire. It was indeed an NVA sapper, and when discovered, he

cranked off several rounds from his AK rifle right at me. However, he aimed

too low, and the bullets skimmed off the berm and grazed the top of my head.

Suddenly all hell broke loose as M-16's, AK-47's, and M-60's rattled

away for almost three hours along with mortars, 105's, and B-40 rockets.

(Note: The fog was too thick for air support, so we were reliant on our

organic mortars and 105's.)

While I was on the radio to my CO, a

chi-com grenade rolled up next to me and detonated. It was thrown by an NVA

that had infiltrated our perimeter and was lying just outside the berm, but

we never saw him. I have to admit he was a pretty cool customer and good at

camouflage. I'm sure he paid the ultimate price for his actions, however,

along with 27 other of his comrades.

My injuries from the grenade

were severe, and it was three hours before receiving any medical attention

as the battle raged, which I missed due to loss of conscience, loss of

blood, and shock. From a technical standpoint, I should have died.

The after-action report, daily log, and manning report listed 28 NVA KIA

(Killed In Action) with numerous blood and drag trails the next morning,

suggesting they probably had more losses than 28. It was a miracle that not

a single GI died in the battle. It is sometimes better to be lucky than

good!

Soldiers told me I was unconscious at about 0600 when the fog began to

dissipate and the sun rose to allow a Medevac helicopter to land and take me

plus eight others of the most seriously wounded to FSB Buttons. Shortly

after that, a Chinook (CH-47 helicopter) landed with an emergency resupply

of ammunition, unloaded, and loaded the remaining 24 wounded and took them

to FSB Buttons.

Soldiers told me I was unconscious at about 0600 when the fog began to

dissipate and the sun rose to allow a Medevac helicopter to land and take me

plus eight others of the most seriously wounded to FSB Buttons. Shortly

after that, a Chinook (CH-47 helicopter) landed with an emergency resupply

of ammunition, unloaded, and loaded the remaining 24 wounded and took them

to FSB Buttons.

I do remember the cold air of the aircraft waking me

up for a moment and asking where I was when I arrived at FSB Buttons aid

station. I woke up to Tom Garnella's voice and getting bumped down some

steps into a cave. Somebody said: “Be careful; he has a broken arm.”

However, I don't remember much of that, which is probably for the best.

I wasn't hurt badly by the AK rounds but was bleeding pretty good. When

the grenade went off, all I heard was a pop, and then it felt like somebody

took a baseball bat to my entire body. I was blinded and deaf but knew I was

in sad shape and attempted to crawl - somewhere. I had a pulverized right

elbow that collapsed, so I kind of snaked my way to a pile of sandbags to do

a little BDA, Body Damage Assessment. My sight started to return, and I

realized I had crawled into one of our scout tents.

As the evening wore on, the tent that I was in looked like Swiss cheese

when illumination was up. I kept getting hit by either B-40 or mortar

shrapnel as I lapsed in and out of conscientiousness. The burning shrapnel

hitting me jolted me awake and probably saved my life. I was evacuated to FSB Buttons and then to

the 24th Evac. They split me open like a trophy deer to fix the damage done

to my liver, kidney, spleen, and other internal stuff. Then they discovered

that I had a piece of shrapnel in the right brachial artery that had been

sent there by my heart. There were two more chunks in the heart they left

alone and are still there to this day unless they rusted away.

After

the flight to Japan, I nearly “bought it.” My heart was still leaking, but

the sac around it had begun to heal, so I had near-fatal pressure building

up, requiring tapping three times before the bleeding stopped.

My

poor parents were subjected to telegrams from the Army, listing all my

injuries in gory detail. A telegram dated 1 July 1970 stated, ”He received

wounds to the back, scalp, abdomen (with hemothorax, lacerations of the

liver and right renal), chest with right hemopneumothorax, and embolus of

the right brachial artery and all extremities. And both eyes had partial

loss of vision to the left eye and corneal abrasions to both eyes.”

Another telegram dated 08 July 1970 stated, “Your son was placed on the very

seriously ill list. He has an additional diagnosis of a wound to the heart,

right lung, right lobe of the liver, right arm, and a fracture to the right

olecranon. In the attending physician, his condition is of such severity

that there is cause for concern. His present condition and prognosis are

noted to be fair and his morale good.”

My ten months in the “brush”

weren't without some excitement. They resulted in awards of the Silver Star,

Bronze Star with V device for Valor and Oak Leaf Cluster, Purple Heart (PH)

with Oak Leaf Cluster, Air Medal, and Army Commendation Medal with V device

plus all the “I was there” stuff. I wanted to make the Army a career, but

they said they no longer required my services and retired me at 100%

disability at the rank of Captain. Anyway, it was an interesting ride while

it lasted.

I got a 100% disability for my trouble and then went into

sales as a manufacturer's rep. My left eye has since lost all sight but have

no regrets and would do it all again. About seven years ago, I decided I was

deserving of a second PH and began the process of begging the Army to grant

my request. I ran into objections like you need two sworn witnesses (which I

didn't have), two MD attendants who treated me (which I didn't have), and

then they told me only one PH per deployment was authorized each individual.

It went on and on with six-month intervals between their responses. They

were jerking my chain, and it took me five years, but I finally got it after

a Congressional Inquiry and a two-star intervention. The low-quarter

personnel LTC who continually trashed my requests got a reprimand much to my

enjoyment.

THE MEDEVAC CREW

Historian's Note: I was delighted to hear from

Dan Brady, who responded to my Facebook post that he was the medic on that

Medevac mission on 14 June 1970. He said, “I'm sure that Jon Hodges was Crew

Chief and Mike Parsons was Gunner that night. I know Oakie (1LT Hank Tuell)

was the Aircraft Commander, and Mr. Trifiro or Mr. Simpson was the Copilot.

I do remember lots of dead outside the wire when we finally got in. Don't

remember how many tries it took. I do remember my one patient, though. Bad

head wounds and face a mess. I had to do CPR on him. I'm sure he was an SGT

or higher or an officer. I didn't find out if he made it or not. Though I'm

getting foggy about many of my missions, that one remained clear in my

mind!”

Hank Tuell confirmed Dan's recollections. Tom Trifiro was

contacted and responded that he could not remember the mission. Greg Simpson

said he was not 100% certain, but quite sure he was the Copilot on that

mission.

Mike Parsons, the Gunner, is reported to have taken his own

life about 30 years after his Vietnam service. No other details are

available at this time.

Dan Brady and several others report trying to

find Jon Hodges, the Crew Chief, but attempts have been unsuccessful, Jon,

if you are reading this, please contact me at

historian@15thmedbnassociation.org .

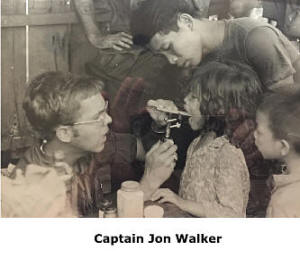

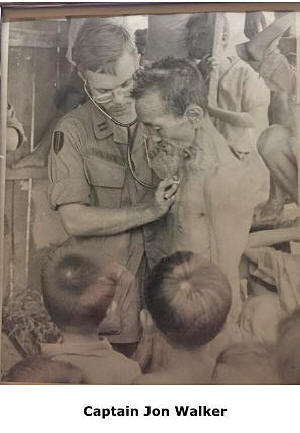

CPT JON WALKER'S STORY

Historian's Note: CPT Jon G. Walker was the 1/5 BN Surgeon, who was at

FSB David on 14 June 1970.

On 14 June 1970, I, Jon G. Walker, was

CPT, Medical Corps, US Army, and I was the Battalion Surgeon of the 1/5

Battalion of the 1st Cavalry Division. At FSB David, my Aid Station was

located near the woods on the southeast perimeter and consisted of a

partially below-grade hole dug by backhoes. My medics and I gained enough

vertical height to stand by creating pillars of sandbags on the edges of the

hole and laying logs across the posts. We then put Perforated Steel Plate

(PSP) strips on top of the logs and covered them with plastic and more

sandbags. The hole was maybe 10’ x 12’. My head medic, an E5 named Rick

Fortune, and I had cots in the Aid Station. A couple of other medics had

built a “hooch” out of corrugated culvert raised on sandbags, which abutted

one corner of the Aid Station.

I had just gotten orders for my R&R and

planned to hitch a ride to the rear area on 13 June to call my wife to make

reservations for Hawaii. I never got off FSB David, however, because the

weather on 13 June was so bad that no one was flying.

For some reason,

neither Rick nor I were sleeping well that night. Around 2:30 AM, we heard

an explosion followed by M16 fire coming from what seemed like the northeast

perimeter of the base. We were immediately up, and it appeared all hell

broke loose. Some of my medics came down to the Aid Station. I was standing

near the opening, where the hooch abutted the Aid Station when an explosion

right outside knocked me across the Aid Station and onto the floor. We

assumed it was a grenade and that another one may land in our hole. That

didn’t happen, so I eventually stood up and shined my flashlight into the

hooch, fully expecting to be shot. What I discovered was that a Rifle

Propelled Granade (RPG) had landed at the other end of the hooch, and the

hooch directed the concussion into the Aid Station where I was standing.

Around that same time, we began hearing calls for “Medic!”

For some reason,

neither Rick nor I were sleeping well that night. Around 2:30 AM, we heard

an explosion followed by M16 fire coming from what seemed like the northeast

perimeter of the base. We were immediately up, and it appeared all hell

broke loose. Some of my medics came down to the Aid Station. I was standing

near the opening, where the hooch abutted the Aid Station when an explosion

right outside knocked me across the Aid Station and onto the floor. We

assumed it was a grenade and that another one may land in our hole. That

didn’t happen, so I eventually stood up and shined my flashlight into the

hooch, fully expecting to be shot. What I discovered was that a Rifle

Propelled Granade (RPG) had landed at the other end of the hooch, and the

hooch directed the concussion into the Aid Station where I was standing.

Around that same time, we began hearing calls for “Medic!”

I was ready to

go out when cool-headed Rick Fortune told me to stay put. I was the only

doctor on the base, and he and the other medics needed to know where I would

be. Shortly after that, I started receiving the wounded. It was chaos, the

ground was muddy, and it was still raining. We were next to a mortar pit, so

as they unwrapped the plastic from the mortar ammo, they would throw it over

to us for use as covers. I quickly assessed each soldier and tried to

determine the extent of the injuries and what action to take. My supplies

were meager.

I had Kling wrap, Ace bandages, gauze, Vaseline gauze,

sterile saline, and curettes of morphine (imagine a small tube of toothpaste

with a needle attached. You put the needle in the patient then squeeze the

morphine out of the tube). Specific injuries remain in my memory: an SGT who

shot in the thigh with an AK-47. The entry wound was small, but the exit

wound in the back of his leg was massive. I packed it with gauze and wrapped

it tightly with an ace wrap, which seemed to control the bleeding. I

remember a soldier with a pneumothorax (collapsed lung), and all I had to

plug the wounds with was Vaseline gauze (maybe LT Chase?). There was another

soldier with multiple shrapnel wounds on his chest and face who was awake

and looked at me when I spoke but didn’t respond.

Additionally there was

a soldier who didn’t look too bad initially but had a massive scalp wound on

the back of his head. I cleaned it with saline, then replaced the skin flap,

and wrapped his head with Kling holding the flap in place. There were

numerous broken bones and lacerations. We splinted what we could and dressed

the wounds but didn’t have the time or the supplies to suture. All told we

had 33 wounded soldiers for about three to four hours. We had no air support

because of the weather and no way to evacuate anyone. When the weather

cleared a little around 6 AM, the first chopper in was a Huey Medevac. I

tried to evacuate the most serious on it and was able to get nine men (as I

recall) out. Shortly after that, I got word a Chinook had just delivered

artillery ammo to the other side of the base and was coming over to evacuate

the wounded. They settled down just outside the perimeter, and I was able to

get everyone else on board. So within five minutes, we went from 33 wounded

to none. As I gradually came back to reality, I didn’t fully comprehend what

had just happened. I was relieved, but other emotions just swirled. I still

remember blood just running in rivulets across the ground.

Additionally there was

a soldier who didn’t look too bad initially but had a massive scalp wound on

the back of his head. I cleaned it with saline, then replaced the skin flap,

and wrapped his head with Kling holding the flap in place. There were

numerous broken bones and lacerations. We splinted what we could and dressed

the wounds but didn’t have the time or the supplies to suture. All told we

had 33 wounded soldiers for about three to four hours. We had no air support

because of the weather and no way to evacuate anyone. When the weather

cleared a little around 6 AM, the first chopper in was a Huey Medevac. I

tried to evacuate the most serious on it and was able to get nine men (as I

recall) out. Shortly after that, I got word a Chinook had just delivered

artillery ammo to the other side of the base and was coming over to evacuate

the wounded. They settled down just outside the perimeter, and I was able to

get everyone else on board. So within five minutes, we went from 33 wounded

to none. As I gradually came back to reality, I didn’t fully comprehend what

had just happened. I was relieved, but other emotions just swirled. I still

remember blood just running in rivulets across the ground.

I eventually

went for a walk with Rick Fortune and viewed at least 28 enemy bodies

outside the perimeter, many of them just blown apart. We thought we heard an

AK-47 near the Aid Station at one point and, indeed, found spent AK shells

on the ground. I assume the shooter was on the roof of the Aid Station. Was

he the one who was shot?

I later found out that Rick Fortune went out

without his “steel pot” to identify him as American. The Sgt Major (whose

name I can’t recall but would like to know) told me he had Rick in his

sights but recognized him at the last minute and didn’t shoot. (Historian's

note: The Sergeant Major was CSM Bell.)

We didn’t lose any GIs at the

base, and I subsequently learned all survived. I’m especially pleased to

know that. I eventually got a Bronze Star with a V, which was certainly a

novelty at my next assignment in the Out-Patient Clinic at Fort Gordon, GA.

And that’s my story. I haven’t been able to find my name anywhere in the

records but occasionally will look. I was the only doctor on FSB David on

that infamous day. I left the Army in the fall of 1971, specialized in

Urology, and am now retired after practicing in Lancaster, PA, for over 30

years.

TOM GARNELLA

Historian's Note:

1LT Tom Garnella was the Medical Operations Assistant at B Co., 15th Med BN

02/70-02/71. Tom also gets the credit for inviting Joel and Dorothy to the

Branson Reunion, thereby getting work on this story started.

Historian's Note:

1LT Tom Garnella was the Medical Operations Assistant at B Co., 15th Med BN

02/70-02/71. Tom also gets the credit for inviting Joel and Dorothy to the

Branson Reunion, thereby getting work on this story started.

When

Joel got to FSB Buttons, he and 1LT Tom Garnella both got the surprise of

their lives! Joel had been an OCS TAC Officer at Fort Benning, GA, and Tom

was one of his officer candidates! Here is what Tom had to say:

“You

are correct that when Chase was brought into the FSB Buttons aid station, it

was I who looked down and immediately recognized him. Like you asked, what

are the odds of my Ft. Benning TAC Officer coming into the aid station to

which I was assigned? Unbelievable!!! Who could ever forget their Infantry

OCS Tac Officer who decided I should be commissioned as a 3506 MOS, Field

Medical Assistant. Concerning Chase, my role was basically to assure Chase

that he would live and that Doc Lundquist and others would take care of him

as we prepared to send him to the 24th Evac. Doc Lundquist allowed me to

accompany Chase to the 24th, where I stayed by Chase's side for two days

before having to return to FSB Buttons“.

A little extra irony was

that Joel had recommended that Tom go into the Medical Service Corps instead

of the Infantry.

Tom mentioned his gratitude to his friend, CPT Dean

Stoller, MC, with HSC 15th Med BN for helping him to connect with Joel Chase

45 years after his tour in Vietnam.

JON LUNDQUIST

Historian's Note: CPT Jon Lundquist, MC, was the Commanding Officer of B Co.

and the physician that treated Joel. He does not explicitly remember

treating Joel because of all the other seriously wounded that came into his

facility.

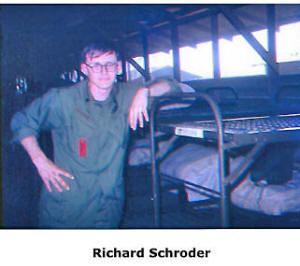

RICHARD SCHRODER

Historian's Note: SP5

Richard Schroder, Clinical Specialist, 12/69-12/70 recalls very well the day

that a Chinook brought in a load of wounded to FSB Buttons. Here is what he

said.

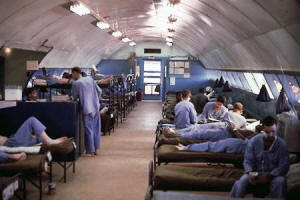

“I do remember very well a Chinook that brought some wounded to

Buttons, and I believe that was the only time a Chinook landed on our Huey

pad while I was with B Company. We had gotten the word that the Chinook was

coming to the Chinook pad with wounded, so we sent our ambulances and medic

up to the Chinook pad to get the wounded. Another SSG 91C and I stayed

behind to get the treatment bunker ready to receive the wounded and to alert

the Docs. I remember the surprised look on our faces when we heard the

Chinook and realized it was landing on our pad. Several of our big GP tents

were acting like giant bellows, but none came down; however, our 50-gallon

trash containers got caught in the downward and were blown all over the

place. We told our clerk to recall our medics and ambulances and to notify

the docs and any off duty personnel as we figured we were going to need help

once the chopper landed. Once the Chinook landed, we started to offload the

wounded by way of the rear ramp (I still can remember the heat coming from

the engines).“

“I do remember very well a Chinook that brought some wounded to

Buttons, and I believe that was the only time a Chinook landed on our Huey

pad while I was with B Company. We had gotten the word that the Chinook was

coming to the Chinook pad with wounded, so we sent our ambulances and medic

up to the Chinook pad to get the wounded. Another SSG 91C and I stayed

behind to get the treatment bunker ready to receive the wounded and to alert

the Docs. I remember the surprised look on our faces when we heard the

Chinook and realized it was landing on our pad. Several of our big GP tents

were acting like giant bellows, but none came down; however, our 50-gallon

trash containers got caught in the downward and were blown all over the

place. We told our clerk to recall our medics and ambulances and to notify

the docs and any off duty personnel as we figured we were going to need help

once the chopper landed. Once the Chinook landed, we started to offload the

wounded by way of the rear ramp (I still can remember the heat coming from

the engines).“

CHINOOK CREW

Historian's Note: Also, heroes

that day were the crew of that Chinook who, after making an emergency

delivery of ammunition, hauled 24 wounded to FSB Buttons. Presumably, that

Chinook would have been from the 228th Assault Support Helicopter BN. An

attempt was made to identify the pilot and crew by postings on several

Facebook pages, including the Vietnam 1st Cavalry Facebook page with some

responses received. Bill Lee, who was Operations SGT with Charlie Co., 228th

ASHB, suggested it was a Chinook pilot with that unit named Bob Barr

(nickname “Cowboy Bob”) who many times did offer to transport wounded under

similar situations. We were not able to find his name on any of the 228th

ASHB rosters, VHPA rosters, or 1st Cavalry Division Assn membership rosters.

I was notified by Bob Braa that he was a Chinook Pilot whose nickname was

“Cowboy Bob,” and that his crew was on standby at FSB David that day, but a

different crew made the pickup of the wounded. Unfortunately, no additional

information was found on the identity of that crew. If anyone reading this

knows, please contact

historian@15thmedbnassociation.org . I

understand it was not uncommon for Chinook crews to transport wounded.

Historian's Note: Also, heroes

that day were the crew of that Chinook who, after making an emergency

delivery of ammunition, hauled 24 wounded to FSB Buttons. Presumably, that

Chinook would have been from the 228th Assault Support Helicopter BN. An

attempt was made to identify the pilot and crew by postings on several

Facebook pages, including the Vietnam 1st Cavalry Facebook page with some

responses received. Bill Lee, who was Operations SGT with Charlie Co., 228th

ASHB, suggested it was a Chinook pilot with that unit named Bob Barr

(nickname “Cowboy Bob”) who many times did offer to transport wounded under

similar situations. We were not able to find his name on any of the 228th

ASHB rosters, VHPA rosters, or 1st Cavalry Division Assn membership rosters.

I was notified by Bob Braa that he was a Chinook Pilot whose nickname was

“Cowboy Bob,” and that his crew was on standby at FSB David that day, but a

different crew made the pickup of the wounded. Unfortunately, no additional

information was found on the identity of that crew. If anyone reading this

knows, please contact

historian@15thmedbnassociation.org . I

understand it was not uncommon for Chinook crews to transport wounded.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS BY JOEL CHASE

Part of the story

about the defense of David that has received “little ink” is the heroics of

Mike Crutcher during the battle. Mike, the CO of the Recon Co, was all over

the place, and at one point, Bill Vowell CO of D Co realized the enemy was

in a few of our bunkers, which was a dangerous development. Bill asked the

adjoining bunker commander if he could move to retake the bunkers, which

were threatening the entire firebase. The response was he "couldn't move."

Mike Crutcher was aware of the conversation and communication and sprang

into action with a small volunteer posse and retook the bunkers from the

enemy which, was a critical move in securing the perimeter. Mike was awarded

the Silver Star for his heroics and eventually retired from the Army as a

Colonel. What a fine and brave young officer!

Part of the story

about the defense of David that has received “little ink” is the heroics of

Mike Crutcher during the battle. Mike, the CO of the Recon Co, was all over

the place, and at one point, Bill Vowell CO of D Co realized the enemy was

in a few of our bunkers, which was a dangerous development. Bill asked the

adjoining bunker commander if he could move to retake the bunkers, which

were threatening the entire firebase. The response was he "couldn't move."

Mike Crutcher was aware of the conversation and communication and sprang

into action with a small volunteer posse and retook the bunkers from the

enemy which, was a critical move in securing the perimeter. Mike was awarded

the Silver Star for his heroics and eventually retired from the Army as a

Colonel. What a fine and brave young officer!

I had learned from the

enemy not to present the expected. They changed things to make a probe look

like an attack and make an attack appear to be just a probe. To counter

that, I had our guys string 25 tripwires and flares in front of each bunker.

They were crisscrossed side to side and front to back - some high and some

low in the grass. Then we moved the claymores back to the berm and

sandbagged them after dark so the NVA didn't know where they were and

couldn't play with them. Note: The NVA were watching us from nearby hills,

so we needed to “play cute” showing our hand during the day and moving

positions after dark. That may not seem important, but as every infantryman

will tell you - take advantage of all available resources.

The NVA

that attempted to overtake David was a combination of their elite sappers

and Infantry. The estimated number was a reinforced company, but I'm not

sure how that relates to personnel in their configuration. The first line of

attackers were sappers who would open avenues through concertina wire and

trip flares of approach for the attackers that followed. They frequently

stripped off their clothing to minimize getting snagged in barbed wire.

Sometimes they wove mats of grass that they put on their backs as

camouflage. When they encountered our concertina wire, they would slither

through it like a snake and continue forward after placing satchel charges

in the wire to blow holes for their comrades when the attack began. Some

sappers would take long blades of grass and "feel" their way through trip

flare wires. If the grass bent, they would find the wire and follow it to

the source, hoping to disarm the trip. Sometimes they guessed wrong and

simply found the anchor to the trip, but they would retrace their route and

disable the tripwire at the other end by pinning it. All this took time -

lots of it. Sappers would typically begin their crawl to the objective just

after sunset and spend as much as three hours weaving their way through

barbed wire and trip flare wires. The weather on 14 June played to their

favor as dense fog reduced visibility earlier than usual, giving them an

early rally point. I had seen demonstrations of how sappers could silently

infiltrate a position that quite frankly scared me. They were good - VERY

good.

To counter the capabilities of the sappers, we installed 25

trip flares in front of the four bunkers in my sector. It looked like the

inside of two pianos going at 90 degrees in different directions. Usually,

our claymore mines were placed just inside the wire. (Claymore mines had

steel balls embedded in a plastic backing and two pounds of C-4 explosive to

propel the balls toward the enemy). Knowing we were being watched or mapped,

we put out the claymores during the day and then moved them back to the berm

to use their impact better and eliminate possible NVA tampering. Yep. The

NVA would take the reflective engineering tape off the back of a claymore,

turn the claymore around and replace the tape as nothing happened.

The Cav beat the NVA best at their own game in defending FSB David. The guys

who waged that battle were mostly enlisted men who did an extraordinary job

of holding their ground and repulsing a large enemy force. I believe their

story deserves retelling and retelling.

To the Medevac crews that

rescued me not only on 14 June 70 but throughout my time in Vietnam: You

were calm on the radio and taught me to do the same, which my guys observed

and served to maintain some sort of organization even under fire. You guys

were the greatest, and I have the highest admiration for you all!

I

always looked forward to getting my guys on birds going out, but inbound

birds meant danger ahead and the unknown. We always knew you were there when

we needed you, which was important.

When you get involved with “bad

guys” and are in desperate need of medical help, the guys on the ground

always felt the choppers with the red cross would somehow come to our

rescue. You made us braver than we were - you guys are my heroes.

To

CPT Jon Lundquist, B Co., 15th Medical Battalion Commander, and CPT Jon

Walker, 1/5 BN Surgeon and their medics and other medical personnel, without

whose skill, determination, and compassion, I would not be here today, I am

forever in your debt!

God Bless you all, and thank you!

Joel

Historian's Note: In closing, Joel has these two stories that have

nothing to do with FSB David but are two of his favorite stories from

Vietnam.

“Our battalion got a new commander, and we were at an

established FSB near the Cambodian border. Our new "leader" decided the

place needed some grooming and ordered all cigarette butts and matches to be

policed by the troops guarding the perimeter. Inspections would be

performed, and if violations were discovered, the personnel at the offending

bunker would get no beer or soda. So I asked my guys to be perfectionists

and deliver their trash to me. After dark, I took a large pail of matches

and butts up to the TOC and scattered them all over the place. I guess

somebody got the message because the inspections stopped. If our fearless

leader had wanted to do something healthy for his troops, he could have

requisitioned a case of rat traps to reduce the infestation of vermin in the

bunkers around the perimeter where we slept. The life of the grunt was

considerably different than other MOS's, and quite frankly, I preferred

pounding the brush to rear echelon duty. ”

“After a few weeks at

24th Evac after being wounded, I was well enough to transport to Japan. I

was ambulatory and picked up my war trophy SKS rifle in preparation for

transport to the airport. A rickety old Air Force blue bus arrived, and a

bunch of walking wounded boarded, and in retrospect, our transport probably

had no springs. It immediately became apparent the driver was a masochistic

bastard because he hit every curb, pothole, and bump on the way to the

airport. He was a real pro at accelerating and decelerating. There were lots

of moans and groans from the wounded passengers, which simply seemed to give

the driver greater pleasure from abusing his passengers. When we arrived at

the airport, we found our flight canceled due to weather, so we pulled a “Uey”

and returned to the 24th Evac Hospital with more bumps and bruises. Same routine the

next day with more passenger agony, which pissed me off, so I fixed the

bayonet on my SKS and began an advance toward the driver. He saw me coming

in his rearview mirror, and I gently pushed the point of the bayonet on the

back of his neck. I said: "OK, asshole, if you hit one more curb, pothole,

or bump, you'll be looking at the point of this thing through a buttonhole

in the front of your shirt - GOT IT?!" It turned out that kid was an

excellent bus driver, and I got a rousing cheer from the other passengers.”

“After a few weeks at

24th Evac after being wounded, I was well enough to transport to Japan. I

was ambulatory and picked up my war trophy SKS rifle in preparation for

transport to the airport. A rickety old Air Force blue bus arrived, and a

bunch of walking wounded boarded, and in retrospect, our transport probably

had no springs. It immediately became apparent the driver was a masochistic

bastard because he hit every curb, pothole, and bump on the way to the

airport. He was a real pro at accelerating and decelerating. There were lots

of moans and groans from the wounded passengers, which simply seemed to give

the driver greater pleasure from abusing his passengers. When we arrived at

the airport, we found our flight canceled due to weather, so we pulled a “Uey”

and returned to the 24th Evac Hospital with more bumps and bruises. Same routine the

next day with more passenger agony, which pissed me off, so I fixed the

bayonet on my SKS and began an advance toward the driver. He saw me coming

in his rearview mirror, and I gently pushed the point of the bayonet on the

back of his neck. I said: "OK, asshole, if you hit one more curb, pothole,

or bump, you'll be looking at the point of this thing through a buttonhole

in the front of your shirt - GOT IT?!" It turned out that kid was an

excellent bus driver, and I got a rousing cheer from the other passengers.”

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to Mike

Bodnar, former Medevac Medic (1/70-7/70) and Editor of the 15th Medical BN

Column in SABER, the 1st Cavalry Division Association's bimonthly newsletter

for research and writing that he has done on the subject of the defense of

FSB David on 14 June 1970. Readers may find his columns in the

November-December 2019 and the January-February 2020 issues of interest.

Go

to the Index, then 2019 Nov-Dec and 2020 Jan-Feb.

Historian's Note: This story is “Mission 20” in Phil Marshall’s book;

Helicopter Rescues Vietnam, Volume XI. This book is the 11th 15th Medical

Battalion Medevac mission included in Phil’s 13 books. Helicopter Rescues

Vietnam, Volume XI, and Phil's other 12 books as well, may be purchased by

going to

Amazon.com.”

If you would like a copy signed by the author with a written dedication, any

of Phil’s 13 books may be purchased directly from him for $20.00 each, which

includes sales tax, postage, and handling. Send cash or check (payable to

Phil Marshall) for $20.00 per book with instructions on what book(s) you

want to order and where to send the book(s) and what, if anything, you would

like in the dedication. His address is 1063 Cardinal Dr., Enon, OH 45323,

the phone is 937-371-3643, and his e-mail is

dmz.dustoff@yahoo.com . You may

also use PayPal. Phone or e-mail Phil with any questions.

[ Return To Index ]